Alternatives to conjoint for identifying optimal feature bundles

A B2B product marketer came to us with an interest in conducting a conjoint study to identify the features to include in their Starter and Pro solution packages. They had used the methodology before and thought it would be a good fit for their needs. We did too. Unfortunately, a combination of budget and practical realities eliminated conjoint as an option. The client was disappointed at first, until we elevated the conversation away from a specific methodology to focus instead on the job-to-be done for the market research. This client needed market research to identify the features to include in the Starter and Pro packages.

While conjoint analysis is great, it is one of many tools in the research toolbox. Using other research approaches, we identified the appropriate feature set for the two packages that bore out in practice when the client introduced them to the market. This post looks at the how traditional approaches and techniques can provide the type of insights associated with conjoint and other trade-off modeling techniques.

Conjoint analysis

Conjoint analysis and its kin are commonly used for packaging and pricing research – especially in consumer research. The distinguishing feature of these methodologies is that they force respondents to choose between a series of features or hypothetical product configurations – they trade-off one thing for another. This exercise comes closer to buying decisions are like in the real world than rating or ranking scales.

So how does conjoint work? In layperson’s terms, the data analysis uses algorithms based on the respondent’s trade-off patterns to identify the relative importance of each feature. These data are then used to build a market simulation model that enables product marketers/managers to see how market demand changes as features are added, changed, or removed from a product offering.

As powerful as they are, trade-off techniques like conjoint analysis have limitations. At their core they work best for products that have a small set of key features that are clearly defined. Examples from the consumer electronics world include weight, battery life, size, # of ports, etc. The reliability of conjoint analysis diminishes rapidly if more than six features are included in the exercise. Many products in the B2B world have dozens of features and functionality which is too many to include effectively in a conjoint exercise. Enterprise software is a good example. Commercial printing presses are another. The features of these solutions can be grouped into broader categories such as integration and customization. However, rolling up features into a category adds ambiguity around what B2B decision makers are specifically responding to when they trade one thing off against another. You lose the specificity of feature trade off the technique is especially useful for.

We also find that when B2B product marketers need market research, they often have multiple informational needs to address in a single study – they only have the budget to do a formal research study every couple of years. Because the number of trade-off tasks required in a conjoint or similar analysis tends to use up virtually all the time available in a survey, there’s little time left in the survey to explore anything else. These points are not criticisms, just the requirements of the technique. Conjoint is a great tool and we use it when it is a good fit for the project goals, as well as the client’s budget and timeline.

What can you do if a conjoint analysis isn’t the right fit or within your budget?

First, don’t get too hung up on a specific analytical approach or technique. Conjoint is a fun tool to use and once someone uses it, they often want to use it again when their next packaging needs arises. Always begin a research study with a focus on the outcome, not the approach. While some are especially useful, there are few approaches that cannot be replicated to at least some degree using other techniques.

Much packaging research in B2B markets uses a traditional survey to explore features individually. From there, thoughtful analysis can identify the features most appropriate for different bundles or packages. A common analysis approach uses multiple ratings to create a matrix and then sort features into different levels to arrive at a score of sorts. In a simple example, scores could be based on the current use of the feature, perceived value of the feature, and willingness to pay extra to acquire the feature.

- Current use: Use today, Plan to use, No plan to use*

- Overall value of the features: Critical, Useful, Not Valuable*

- Willingness to pay extra: Yes, Maybe, No*

*Illustrative scales

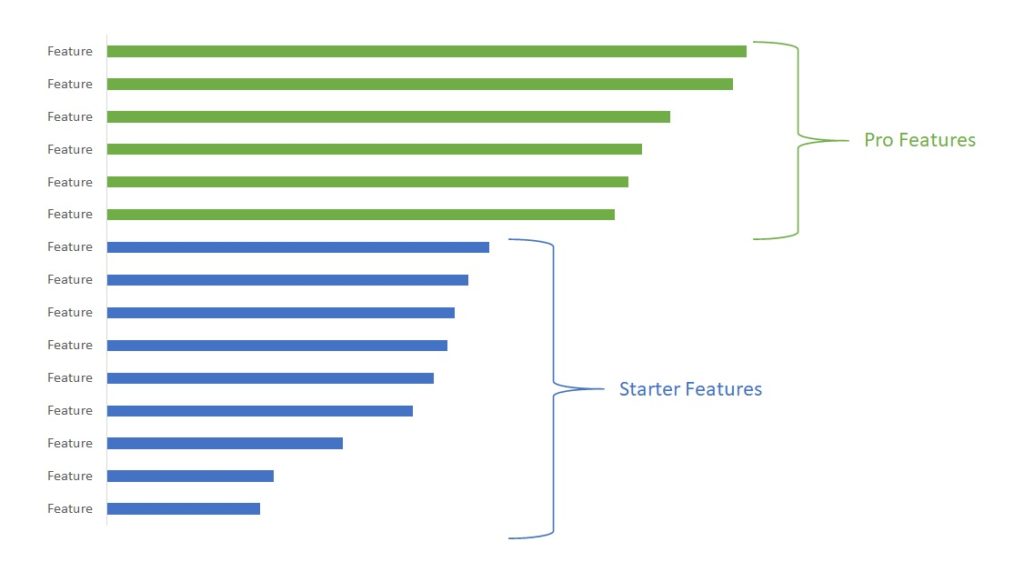

Features which prospects view as critical and that they are willing to pay more to receive will score higher than features viewed as useful but not necessarily worth paying more for. Normalizing the scores can identify the features that prospects value most. Returning to the example that we started with, it can identify the features that make the most sense to include in a Starter vs. Pro package.

This type of analysis can also identify the features that appeal to a narrow market segment that is willing to pay a premium to receive.

This example is just one approach to identify the features most important to the market. A technique called Max-Diff is specifically designed to help prioritize features. And well-crafted surveys using basic analysis techniques such as regression and correlation can shed light on preferences. The drawback of these techniques relative to conjoint style analysis is they lack the ability to run simulations. In a conjoint you can tweak product configurations to see how the changes impact interest in the product.

However, many B2B product marketers seek a broader answer. They need to develop an offering that will appeal to their market, which often includes multiple verticals, often with varied needs.

What’s the right tool?

There are many research tools and techniques available. The right tool is one that aligns with practical feasibility, budget, core informational needs, and the decisions to be made.

For more information about conjoint and other research techniques contact us here.